Good books must haunt the sleep of dictators. Think of the books that have been banned in the last century—The Gulag Archipelago or Satanic Verses, for example. If the man who controls the generals who give orders to the soldiers who blanket the land, clenching rifles and handguns and grenades, working checkpoints and storming homes and hurling chaos into otherwise still nights, if that man also has to stop a printer from laying certain configurations of ink on paper, then that writing must have gotten to him somehow.

We were made to think about censorship when we heard the story of a friend of ours who found a way to buy books someone didn’t want her to buy while in Cuba. Charlotte Rogers is an assistant professor of Spanish at George Mason University and the author of Jungle Fever: Exploring Madness and Medicine in Twentieth-Century Tropical Narratives. She was on the island doing research and participating in a conference at the Alejo Carpentier Foundation. But she also set out for a hands-on experience of how the literary market in Cuba works. We asked her to re-tell the story of her search for “impossible to find” books.

Q: How did you end up buying, shall we say, unofficial books in Cuba?

One of my goals in being in Havana was to explore the book market and the book scene and see who was being published and what people were reading.

I had with me a list of some of the Cuban authors that were big in the 1990s and 2000s. They’re writers who at times have been published in Cuba and, at other times, if their novel is a little closer to the edge of acceptable discourse, you can’t find their work in Cuba. I wanted to see that for myself.

The first thing I did was take a walk with a friend of mine who is a Cuban artist on Calle Obispo, which means Bishop’s Street. They have lots of used and new booksellers. What I found in the established bookstores was that they did have titles by the authors I was looking for, but those titles tended to be erotic fiction. I think discontent with the system and interest in pushing the boundaries is displaced onto erotic fiction. They can push the envelope there because it’s not explicitly political.

Every place I went I would show the booksellers my list and they would say, “I really can’t get this. It’s impossible to find this.”

On the second day, I met up with a friend of mine who is a philologist, so she’s a Cuban literary professor. She gave me a list of intersections where I could find what are called, libreros particulares, which are itinerant booksellers. They have kiosks they can set up on any corner. So the next day we went from corner to corner all over the place. Half the people weren’t there and the other half would look at the list and then they’d look at me and not really be sure why I wanted these books, and they’d say, “No, sorry, I can’t get that. That’s impossible to find here.”

The second day was feeling fruitless, until we went down to the Plaza de Armas.

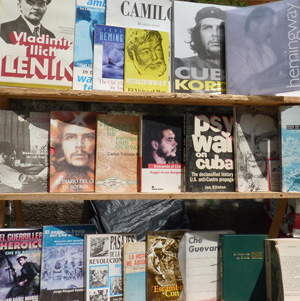

The Plaza de Armas is a very traditional Spanish square. The Havana Harbor is at one end, and there are colonial buildings around it. The square is cobblestone with patches of palm trees and a very lovely garden. All around the perimeter of the square there are booksellers who sell used books, mostly to tourists. Everything is Fidel’s memoirs, and Che Guevara, and cookbooks in English. It’s also swarming with hordes and hordes of tourists.

My Cuban friend happened to know one of the booksellers. So she went over to him and showed him the list. He said, “I don’t have any of that stuff here, because selling it in the main square is a very official commercial task. Why don’t you try talking to that guy?” He sent us to the other corner of the square. Then we talk to that guy, and he says, “Why don’t you try this guy?” and sends us to the other corner of the square. All of this under the tropical sun. I’m hungry. I’m thirsty.

Finally, at the end of the day, everyone was starting to pack up their books and we’re introduced to one last bookseller. He takes my list and he looks at the list, and he looks at me hard. He looks back down at the list, and he says, “Why are you interested in these books?”

I had to be interviewed by him and pass the test.

Q: What do you mean? What questions did he ask when he saw the list?

He wanted to know how I heard about these books. I told him I was a professor of literature in the US and that I had come to participate in the conference and to do research at the Alejo Carpentier Foundation—an author who I work on. He died in ’79, and so he straddled the revolution, but he always paid it lip service. I told the bookseller I was there to research this official writer, but I was really interested in more contemporary Cuban fiction. That gave me enough credibility for him to keep going.

Then he also looked at the list and said, “One of the authors on this list doesn’t belong to this group.” My Cuban friend had added a couple titles that were from a previous century. He immediately picked this out. He said, “If you’re interested in this contemporary stuff, I’m not going to show you this stuff from previous centuries.” That was a signal to me that he knew all of these titles I was talking about.

He looked at the list again for a long minute, and then said, “Yes, I can get these.” After hearing no for two days, I did a double take.

He handed me his business card, and said, “Come to my house tonight at five o’clock, and I think I can find what you’re looking for.”

Q: What was that like?

His house was on a quiet side street with those typical bougainvillea trees. Like every Cuban house, it has a gate out front and beyond the gate there is a very lush patio with rocking chairs and the entrance to the house itself. He had a giant flat screen TV, which is indicative of having family in Miami.

I didn’t get to see his library or warehouse where he kept everything. He would bring the books out to me. He wouldn’t just bring the titles I had asked for, he would bring other titles by that author or things that he thought I would like to read based on what I had given him on the list. It was clear that this man had an amazing ability to get all these books, but he had also read them all. It was an absolute gold mine to sit there with this Cuban man with whom I wouldn’t otherwise have anything in common except that we both loved these books.

Q What do you mean he brought the books to you?

I was in a sitting area near the foyer in his house, and he had a back room where he was keeping the books. So I would sit there patiently, and he would take my list and come back with a stack of four or five books, and we would look them over and talk about them. And some of the editions were good quality, and some of them were really poor. I would say, “I’m really interested in this but not that.” And he would say, “Let me go back and see what I’ve got.” He’d go back in the room and then come out with another stack of books. I probably looked at 40 books while I was there. I only brought a little money with me so I wouldn’t give in to the temptation to buy everything. Nonetheless, my suitcase was at the absolute limit when I flew out.

Q: Did you also talk about why it was so challenging to get some of these titles?

It’s very hard to ask about censorship in Cuba. It’s very hard to ask why you can get certain books and not other books. But as I talked with this man he explained to me that often what happens is that the government doesn’t want to be accused of censorship, so it will publish an author whose work is on the edge. But they say they are going to publish 1,000 copies, but actually only publish 100, and those 100 copies can go in a box and be sent to a provincial bookstore way out in the countryside. So, that author has been published but you can’t get it in Havana.

It is possible to get things, but it’s not easy. In Cuban Spanish, there’s an expression “no es fácil.” It just means nothing is easy. It’s not easy to get anything. There’s the official line, which is always blatantly untrue on the street. Then there are always so many layers to what it takes to get something. Is it out there or is it not out there? And that extends from bread and vegetables to books and shampoo. You might not find it at the first ten stores you go to but if you go to the 11th maybe it’s there.

Q: There seems to be a power in these books. The government wants to control them. People are willing to go to great lengths to get them. What made some books dangerous?

Most people see an opening up of what’s acceptable in Cuba since the 1990s. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the Cuban economy collapsed. They were just trying to feed people and not so concerned with censorship. I found that with some writers, their early work could definitely be published in Cuba. They might be critical of the Cuban way of life in the sense that it was obvious things were closed up and people were poor. That form of criticism has generally been accepted. One of those authors, Pedro Juan Gutiérrez, for example, his later work became more explicitly critical of the gulf between people who live in exile and people who live in Cuba. As it got a little more strident, suddenly, you can’t find a new Gutiérrez book in Havana. These authors often have to start publishing in Spain. And once they start publishing in Spain, there’s usually a window of about a year before they leave and live in exile.

The thing that’s so hard for Cuban authors and artists is that their work is worth more when they live in Cuba. Once they leave Cuba, they lose that cachet of writing behind the curtain. I think that’s the difficult truth—that in order to be considered legitimate as a dissident artist, you have to live under the oppression.

Q: Do you think any of this has an effect on which stories get told or the importance of storytelling?

In Cuba, you never know what the truth really is. What the government says is usually incorrect, and rumor becomes almost consecrated as something you can trust or it acquires a much greater level of social importance than we give it here. So storytelling becomes an art of, can you make your story the most believable? And you can kind of create your own truth. That reveals the importance of storytelling in Cuba for sure.

Q: It sounds like stories are spread more person-to-person in Cuba, like the books are handed from person to person without going through an official channel.

Absolutely. There’s even a saying for that in Cuba. It’s called sociolismo, which is a play on the Spanish word socialismo, or socialism. A socio is like a business partner or a friend, and with socialism failing, people turn to sociolismo, which is based on the exchange of favors, goods, and services among friends. The way people tend to get things is, if one person works in the bread factory, they can borrow a few loaves for their friends, and in exchange you give them nails if you work at the nail factory. So you have a whole network that’s completely off the radar. Cubans pay lip service to socialismo, but they really practice sociolismo.

There are all these great word plays in Cuba. They’re a form of double speak; you say one thing and it means something else. So language itself is impacted in a really twisted way, where official discourse sounds like one thing, but if you go to a slightly different tone or change one letter it means something very subversive, and that’s how Cubans survive, I think.

Q: Do the authors you were looking for have reputations outside Cuba?

I knew about them from books by North American scholars about Cuban literature in the ’90s and 2000s. I had culled the list of people I hadn’t necessarily read or I had read one thing and I wanted to find more. Some of the authors have been published outside Cuba, but I was looking for the works that you can only find there.

One really interesting thing to me was that the bookseller knew what was being published in Spain and what in Miami. How did he know that? Because he’s not supposed to.

Q: Seems he was good at collecting resources, whether books or money or information.

In Cuba, you get used to things not working. The doorbells don’t work, the cars don’t work. I got to his house, and there was no bell, so I used the Cuban shouting-over-the-fence technique, and he comes out, and he says, “Why didn’t you ring the doorbell?” And he points to the doorbell way up high where I didn’t see it.

As I said, his house was very nice. He had good shoes, too. When someone has really nice shoes, it indicates they have family outside.

Q: What counts as nice shoes?

Leather, with a sheen to them.

Another play on language has to do with having family outside the country. If you walk into a really nice house and you see a flat screen TV, and you ask, “How did you come up with all of this?” The person might respond, “Tengo fé,” which means I have faith. It means you have faith in god or the Cuban system, but if you read it in a subversive way, faith, f–é-, could also mean Familia en el Extranjero, family outside Cuba.

Q: Now that you found these books, have you gotten to read them?

I haven’t read everything yet. I still have this suitcase of books upstairs, which is like an unopened treasure.