We were recently at a birthday party. It was the kind that’s held at a bar with no arrangement with the management, and thus no free drinks or private space. The celebrants stand together for a while, and then seem to forget the occasion, and filter into the normal mayhem of a Friday night.

So it was that we found ourselves standing at the bar next to someone who looked just familiar enough that we thought he might be a part of our nominal party. He was older than us, with some grey in his beard, but not so much that he was ruled out as a fellow. We soon found ourselves muttering about the mysteries of human behavior and why people just fall into the same desultory flirtation even on an occasion that should lead to something better. We found the sight rather depressing.

“It’s just the payoffs,” said our companion.

We asked for clarification.

“People do what they think will bring them the most pleasure at the exchange of the least pain. We can agree on that, right?” Certainly. “So, you just need a mechanism to reveal what choices people are making, even if they have no idea themselves.”

We asked for an example.

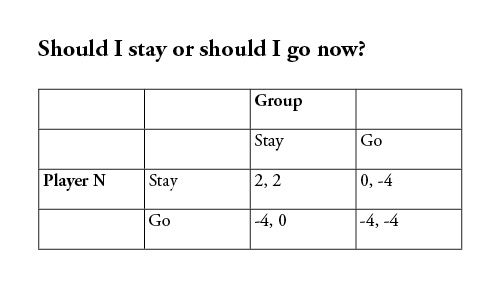

“Here’s the problem your friends face.” Taking a cocktail napkin, he drew a chart that looked something like this:

“You know people always think there’s something better on the other side of the fence, right? Just the fact that your friends came here was a tacit acknowledgement that they’re really looking to meet new people. So, they get here, meet up, enjoy each other’s company. That’s shown here, where everybody stays and gets this nice payoff of two. That represents a pleasant time. But, as soon as the bar starts to fill up and they see lots of other potential conversation partners, shall we say, they start to feel like the potential for big payoffs is in the unknown crowd. They drift off. One after another, they chase that four.”

But then why are these nights always so disappointing? Why do we go home alone or, worse, with someone dreadful? Why do we wake up the next morning sick in both body and spirit?

“The real payoffs look more like this, sure.” He added just a few strokes to the chart.

“But it only matters what people think before they make their decision to stay or go. People keep thinking the four is out there.”

But we do it over and over. Why?

“I can’t explain why. I can only tell you what I observe. Alcohol has something to do with it, I think.”

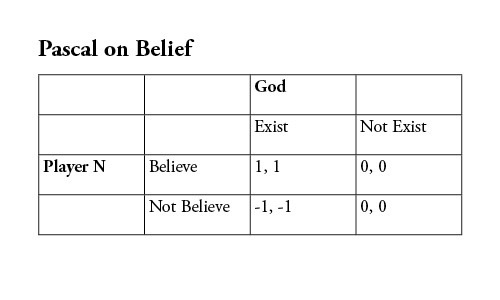

We were interested in this way of thinking, and our friend assured us that it could explain any human behavior. What about religious belief? we asked him, hoping to venture into terrain so inimical to mathematics and logic that he’d falter. Instead, he said, “Pascal famously discussed belief, saying that people are better off believing God exists than not believing He exists. If you don’t believe that God exists, and you’re wrong, you are damned. Eternally. However, if you believe that God exists: ‘If you gain, you gain all; if you lose, you lose nothing. Wager, then, without hesitation, that He exists.’”

And he drew this:

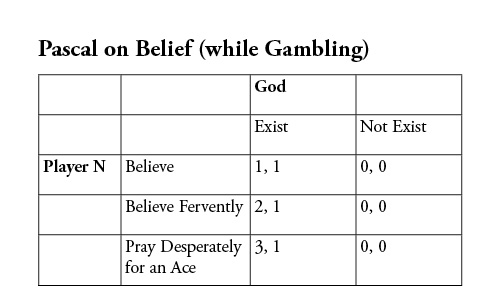

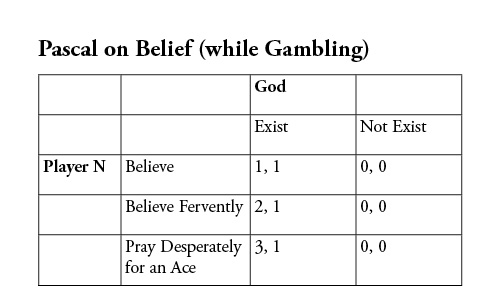

“But Pascal was an inveterate gambler, and this would naturally affect his perceived payoffs to religious belief.”

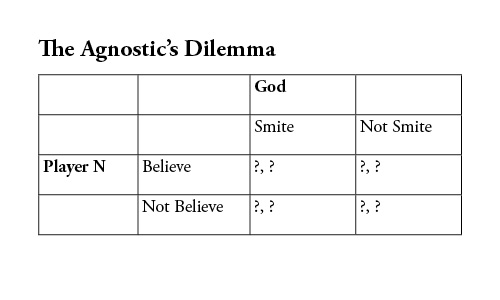

“Now, some people can’t decide whether it makes sense to believe or not. You might interpret that as their being uncertain about the payoffs.”

“But I think it’s more likely that this sort of uncertainty stems from a payoff set more like this, where the player always finds reasons to think about more possibilities.”

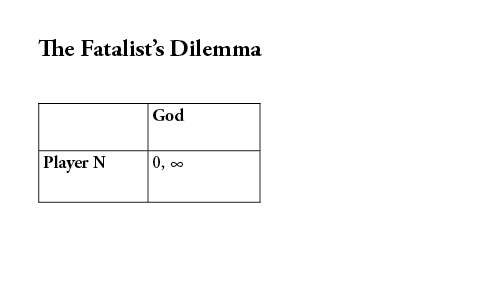

“The opposite of this, which can also lead to a sort of paralysis, is fatalism.”

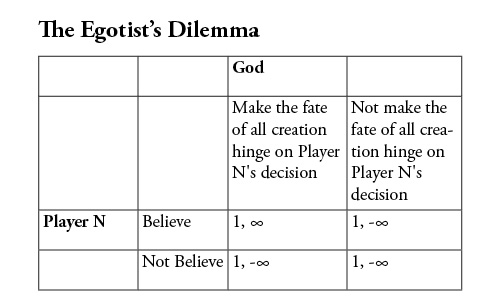

“It’s important to realize that these perceived payoffs are subjective, and that is the basis by which people make their decisions. Take the case of an extreme egotist.”

“You see here that the egotist doesn’t care whether he believes in God or not, while at the same time thinking God will benefit immensely from relying on the egotist. Or perhaps this would be a more immediately germane example of egotism.” He nodded toward one of our friends shaking his arms over his head and making a fool of himself on the dance floor.

We were convinced. The lesson we learned in that bar that night was that we’re all just players looking for a big payoff.