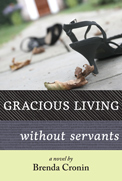

Brenda Cronin is the author of Gracious Living Without Servants, the latest Stoneslide Books release. We asked her a few questions about the novel, why she believes in writing about places she knows, and how journalism has taught her to be a ruthless writer.

Q: You work as a journalist, what led you to write a novel?

I knew shortly after I learned to read that I wanted to write fiction. I was mesmerized by reading books and telling stories, so novels just seemed inevitable. However, I also had an early affinity for journalism. I am child number eight in a family of nine children, so there always was quite a bit going on in our house. My sister who is closest in age to me, just two years older, was often like a twin sister when we were growing up. We had a dear friend, also a girl our age, who lived across the street, and the three of us were inseparable throughout childhood. We began a newspaper together and at first would write about what was going on in our house. It was a terribly primitive thing, just a collection of mimeographed pages, all hand-written and with our own illustrations. We started with articles that stuck to the facts, such as reporting what we had for dinner and what I saw when walking our dog. That was terribly dull, so I started getting a bit fanciful when writing the weather forecasts. When that got tame, we began writing articles about scandalous things we imagined the neighbors were up to. I remember my parents reading our “papers,” dying with laughter – and then burning them, to make sure the neighbors never saw any of it.

Pre-Order Gracious Living Without Servants

Gracious Living Without Servants will be published on October 7, 2013. Pre-order a copy today.

Amazon

Sign up for the Stoneslide email digest for further updates on this title.

Q: How did you come to be an economics writer? Are there similarities in writing about economics and literary writing?

I have spent most of my career in financial news, first with Knight Ridder and then with The Wall Street Journal. I joined the Journal in 2001 and worked as an editor on the national and international news desks in New York. I’ve largely stuck to economics and politics, as both strike me as interesting and related to pretty much everything of import that is happening. After two years as the paper’s Economics News Editor, I switched to covering economics early in 2013. It was a big and delightful change—I report and write my own stories.

Q: Have you learned anything from newspaper writing that has informed your prose style?

It seems to me that the Journal has a style and a voice that are harmonious with mine for non-fiction. While I would say my non-fiction writing has improved thanks to working at the Journal, the paramount lesson I have learned here is practicing economy of words. (My bureau chief doubtless would say I have a great deal more to learn in that department, as I consistently file to him articles that are considerably longer than promised.) Although cyberspace presumably is infinite, a newspaper isn’t, and nothing sharpens the mind and focus like a set space in which to tell a story. So, the Journal has taught me how to be ruthless in choosing what to include in the story and also what to jettison; to avoid using jargon, which often is a clue that the reporter is lazy or doesn’t have a firm grasp of her material and is just parroting back what sounds persuasive.

Q: How did you manage to both write fiction and report?

The two practices are very different! It really does feel as if a certain switch goes on or off in the brain when moving from one to the other. For one thing, reporting and then writing an article feels to me like a distillation process, of just bringing up the few perfect pieces that crystallize a story. While the same should be true in fiction—where one writes pages and pages and ends up preserving a few paragraphs—the process of producing that great big mass of first-hand raw material is completely different for a novel than for a story. In reporting, I am conscious of trying to get in all sides, to reflect many viewpoints and interpretations of a given subject. In fiction, I am expressing a situation from a particular point of view—perhaps one character, perhaps through the eyes of an omniscient narrator—but the lens is narrower and targeted. On another note, when I write for work, I am always imagining not only a subscriber but also an editor examining my work. I am constantly asking myself, “Is this sentence clear? Is there any ambiguity in that phrasing? How can I make this absolutely clear and fair?” When I write fiction, I don’t think about readers—as I don’t have any expectations of audiences!—and, at least in the first draft phase, it’s a delightfully fast and flowing process. Of course, I end up saving about 10% of all that ink, but the initial torrent of putting it on paper (and I do my first drafts in longhand) is exhilarating.

Q: Your protagonist, Juliet, also works as a journalist. Do you sympathize with her drive to get a story? Is that a part of your life?

Yes, that drive should be a critical motivator of any journalist—but I wouldn’t recommend the means by which Juliet gets her story! Competition to be first and excellent is a constant in our work, particularly in this world of continuous online news. The expectation in my work is that all reporters and editors, anywhere around the globe, are always thinking about how to make our work stand out. We’re always looking not only to be the first but to have the most interesting and well-thought-out story. Much of the time, it’s a matter of discerning a story out of a big mass of data, or finding an interesting pattern in what at first blush appears to be many random events.

Q: Your book is set in a fictionalized version of New Haven, Connecticut. Why did you choose to set it in the city where you grew up?

Within limits, I believe in writing about places that one has a pretty good handle on. I think readers cotton on very quickly—and tend to fall away—when they sense that a writer is literally on shaky ground when it comes to the fundamental setting where the story unfolds. So, while there certainly are more glamorous or exotic locales than New Haven, I thought it wise to keep to terrain where I could feel so authoritative and sure, it would just flow naturally in the story. Also, the place really is something of a character in the story. Gracious Living wouldn’t be the same if it were set, for example, in New York City, where I live. The small city—and particularly the neighborhood—where the novel is set are essential. And I have enormous fondness for much of the city, so it was fun to set scenes in places where I spent my childhood.

Q: Do any of the events from Gracious Living Without Servants come from your life?

Happily, no! While I am a journalist, I write about economics, not the arts. My former husband is alive and well, so I am not a widow. And I don’t think I would go about my reporting in quite the way Juliet does—because I wouldn’t like to be fired! However, all the news events that are cited in the background not only are real, they are part of the tale—the Clarence Thomas confirmation hearing, the first Desert Storm. I was in Washington, D.C., during both, and associate them with a particular time I wanted to capture in the novel.

Q: Did you know people like Seth and Naomi when you were growing up? Did you particularly enjoy writing about these two characters?

Yes, growing up in New Haven, I had plenty of friends who had one or two parents with careers in academe. And although I doubtless missed many of the nuances in the conversation around their dinner tables and our own, I was certainly aware of what it was like to have careers – at a university or college – where there was keen but subtle competition that extended well beyond the classroom. I loved writing about Seth and Naomi. Even though both are doubtless flawed, I grew very fond of them and had to work—I hope successfully— to keep their solipsism from sailing into caricature.

Q: Seth is 35 years Juliet’s senior. Why is she drawn to him?

As a rather fragile widow who is just tiptoeing out of her mourning, she finds a successor to her husband unthinkable—and yet she is ready to inch ahead with her life. Seth represents someone who lives up to her memories of Alex, which, of course, have only become more gilded with his death. Seth represents two delightful prospects for Juliet: both a scandalous adventure, and yet one with a man who already has—in almost every aspect except the obvious—earned the respect and admiration of her family. He is brilliant, polished, handsome, refined—and, of course, completely self-absorbed and unfaithful to his wife. In short, Juliet finds him perfect for her first foray back to life after Alex.

Q: The novel takes place against the political backdrop of the Anita Hill/Clarence Thomas hearings. Why did you choose to weave in those real-life events?

Real-life events – the sexual harassment theme that electrified the nation during the Thomas hearings and the equally ominous themes of loss and sadness that surged with the first Gulf War—serendipitously fit well with the themes of the novel. Both also, in my view, were part of defining a stretch in time—before the Internet, before email and cellphones—that in turn also affected how people communicated and conducted relationships. I wanted to write about that era, before there were so many ways to stay in touch.