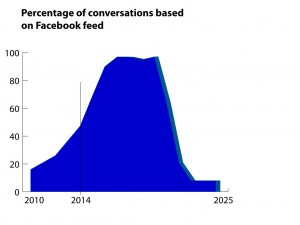

A new study out of Upland Downs University has found that nearly half of conversations in the real world start with some variant of, “You know what I just saw on Facebook?” The study used observers placed in coffee shops, train stations, and public parks to record thousands of unprompted exchanges between friends, family members, and complete strangers, and found that 47.2 percent of conversations that could be observed depended on material posted in a speaker’s Facebook feed. This rate was up from 26% two years ago and just 16% in 2010.

The lead author of the study was Lavinia Loope, a professor of communications at Upland Downs, and she argues that this phenomenon is driven by the “lowest conversational denominator effect.” Says Loope, “It takes energy and effort to sustain any conversation, and so people will naturally look for the lowest effort point of shared interest or knowledge. Today, that low point is Facebook.” She also points out that people crave approval, and repeating something funny you saw on Facebook is an easy way to get that reward.

The lead author of the study was Lavinia Loope, a professor of communications at Upland Downs, and she argues that this phenomenon is driven by the “lowest conversational denominator effect.” Says Loope, “It takes energy and effort to sustain any conversation, and so people will naturally look for the lowest effort point of shared interest or knowledge. Today, that low point is Facebook.” She also points out that people crave approval, and repeating something funny you saw on Facebook is an easy way to get that reward.

The study, which was published in the Journal of Implied Outcomes, also predicted that the percentage of conversations based on Facebook will peak at 97% in 2017. At that point, nothing new will be posted on Facebook, due to the fact that everyone will only be talking about what’s already on Facebook. This will usher in what the researchers call the “helicopter phase,” in which Facebook memes will go around and around, keeping the percentage of conversations based on Facebook at 97%, until everyone realizes that they’ve seen and talked about everything on Facebook already, at which point the percentage will collapse.

The study, which was published in the Journal of Implied Outcomes, also predicted that the percentage of conversations based on Facebook will peak at 97% in 2017. At that point, nothing new will be posted on Facebook, due to the fact that everyone will only be talking about what’s already on Facebook. This will usher in what the researchers call the “helicopter phase,” in which Facebook memes will go around and around, keeping the percentage of conversations based on Facebook at 97%, until everyone realizes that they’ve seen and talked about everything on Facebook already, at which point the percentage will collapse.

For those readers curious about what the future holds, the remaining three percent of conversations will be about traffic, weather, and intestinal ailments. Those subjects cannot be completely eradicated.

The researchers used two models to form these hypotheses, one from the world of epidemiology and one based on studies of the changes in predator and prey species populations over time. “Whether you think of Facebook as a parasitic streptococcal bacterium or a vicious member of the mustilidae family, commonly known as weasels, the result is the same,” says Loope. “Facebook destroys normal conversation up until the point when there are no hosts or prey left, and then Facebook collapses.”

The paper also discusses some of the likely effects of this boom-bust cycle on other aspects of daily life and economic activity. For instance, by the first quarter of 2018, Facebook will employ 12% of the global population. The eventual implosion of the company will lead to global economic depression. Given the tendency of videos and photos to draw more attention than plain text on the social network, literacy rates will decline by 26% worldwide and the art of writing will largely disappear, being sustained only in a few remote places without broadband access.

The paper also discusses some of the likely effects of this boom-bust cycle on other aspects of daily life and economic activity. For instance, by the first quarter of 2018, Facebook will employ 12% of the global population. The eventual implosion of the company will lead to global economic depression. Given the tendency of videos and photos to draw more attention than plain text on the social network, literacy rates will decline by 26% worldwide and the art of writing will largely disappear, being sustained only in a few remote places without broadband access.