by Wilford Eksale, Professor of Economics, Wye Sprite University

This commentary originally appeared in the Journal of Implied Outcomes Online Edition and is reprinted with permission.

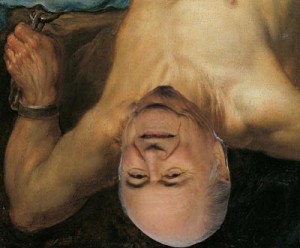

When you see a man like Sepp Blatter, or any of his fellow grandees in the international soccer regulatory body FIFA, laid low by corruption charges, it is not shameful to shed a tear or two. The spectacle of incrimination and accusation currently underway in our courts and our news media is, in many senses, an attack on human genius, and thus an attack on what is best in all of us.

I am aware that these events are not generally understood in this light. The gut reaction of the masses of humanity is to join the phalanx of finger-pointers. But recent research is showing that self-interested and exploitative behavior by elites, like the actions of the FIFA boys, is value-creating and in some cases even heroic.

I am aware that these events are not generally understood in this light. The gut reaction of the masses of humanity is to join the phalanx of finger-pointers. But recent research is showing that self-interested and exploitative behavior by elites, like the actions of the FIFA boys, is value-creating and in some cases even heroic.

I have been studying perceptions of corruption for more than 15 years now. And in a series of studies conducted with my co-author Wapp Wattersnek, I have uncovered a startling fact about corruption and its role in our society—which can in certain cases be salutary.

Our study, originally published in this journal two years ago [ed. note: The Journal of Implied Outcomes] found that instances of corruption among high-status individuals can help advance their organizations—whether businesses, NGOs, or government agencies—and create benefits for many people.

In one set of experiments we showed research subjects a short film in which the CEO of a major retail chain called “Luxomax” solicited a kickback from one of his company’s suppliers. In the film, the CEO receives $2 million in a briefcase. A control group saw a film in which the CEO and the other executive merely discuss the weather and its impact on their respective golf handicaps. We then surveyed all participants about their impressions of Luxomax as a company. Unsurprisingly, those who saw the “corruption” film rated the company lower on measures of integrity. However, they also rated the company’s products as more desirable, and when asked to guess the company’s annual profits came up with answers, on average, $50 million higher than those of the control group.

What’s happening here? Shouldn’t we all be suspicious of an organization led by an evident crook? Well, it turns out that the bribes paid to the CEO are seen as a measure of that CEO’s genius and ability. Anyone who can turn a situation to his or her advantage to the tune of $2 million, the thinking goes, must have great abilities. We are awed by the audacity and acumen required for this accomplishment, and we assume the same abilities will steer and benefit the CEO’s company.

One follow-on experiment helped us further explore the topic. In this case we showed participants a film of a low-income shopkeeper seeking a kickback of a pack of Camels from the driver of a supply truck. In the survey, respondents took a dim view of the shopkeeper’s morality, and also gave his shop poor marks for quality of goods and profitability. Why the difference from the wealthy corrupt CEO? The size of the bribe. We are not impressed by the acquisition of a pack of Camels, and so are not impressed with the corrupt leader or his or her organization.

Let’s think more about how this dynamic plays out in organizations. The brazenly and successfully corrupt leader will transmits a message of capability and vision. This is what the literature calls “inspiring leadership.” His or her employees will be more motivated and will work at higher levels of productivity and creativity. The organization led by the corrupt CEO will in turn create more value for society. (It is no coincidence that soccer is the world’s most popular sport.) The small-dollar cheat, on the other hand, will drag his organization down, prompt distrust and caution in his dealings with other actors, and generally produce that bane of economic health—stagnation.

The lesson is clear—corruption practiced by elites is not only acceptable, it is a boon to society. While laws should target small-time graft, extortion, and skimming, we need to ensure that the super-rich be free from the threat of punishment for actions that, yes, enrich themselves but also enrich us all. Look at the genius of American campaign finance laws by which a billionaire can buy influence over a politician free and clear but any schmoe offering free cigars can get locked up. Or think over the inimitable “corporate governance” system by which CEOs appoint boards who then award the CEO pay packages of hundreds of millions of dollars and call that oversight. These are acknowledged forms of corruption glossed over with technical legality and they are an inseparable part of what makes the American politico-economic system great.

So, yes, I say weep for Sepp Blatter, as you would weep for the blunting of your own genius. That a tragedy is little understood does not make it less of a tragedy.