by Christopher Wachlin

[All of the people were hurt in the writing of this story.]

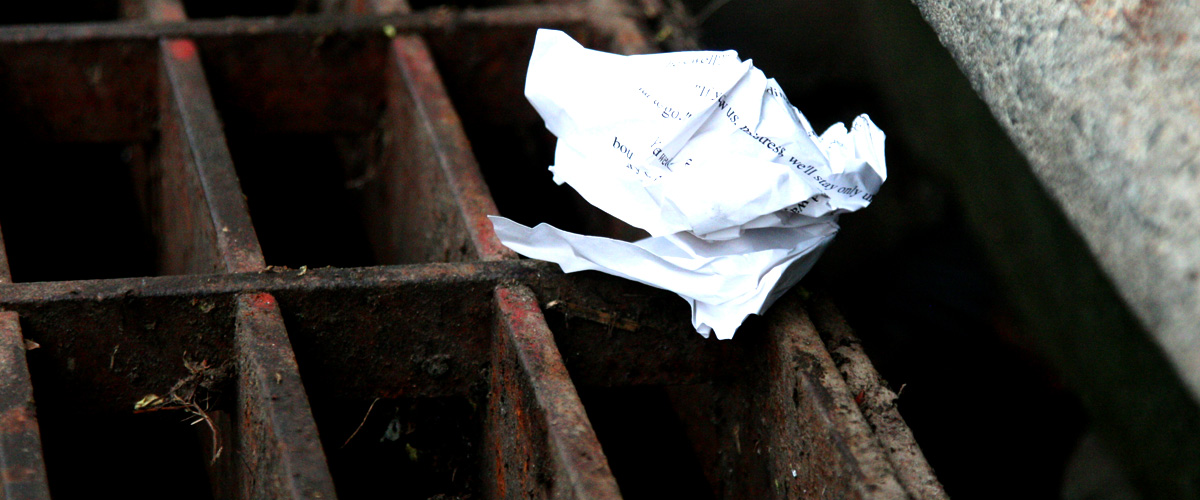

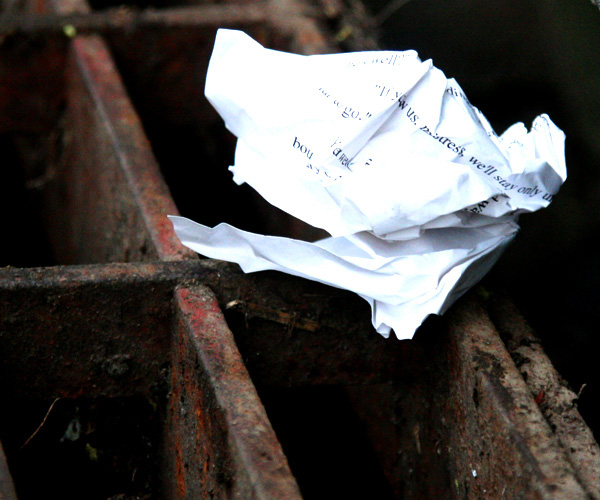

Beneath a moon sliced cleanly in half, Jason reread the note—his suicide note—and then crumpled it up. He stepped off the sidewalk into the gutter and squatted on his haunches. He pushed the note through a sewer grate. The note fell, but got caught in the spiky branches of a seedling growing sideways out of a crack. He found a stick and knocked the note free and it fell again, all the way. Now it would end up in San Francisco Bay, where he hoped to end up. He stood. He pushed his shoulder-length hair behind his ears. He looked skyward, at the halved moon, at the stars, and, across the bay from where he stood in Berkeley, the twinkly San Francisco skyline.

Jason turned around and walked back across the street. His neighbor Korporlundt was in his sloping driveway, bent over the engine of his big Cutlass Supreme. His butt crack rose half a foot above his jeans. Korporlundt was older, in his thirties or forties, one of maybe ten people on the block who wasn’t a student. He had a trouble lamp hooked to the underside of the raised hood. Attached to the lamp’s dangling cord was the head and part of the neck of a jack-in-the-box, its crown shiny gold and its face white as butcher paper, with Xs for eyes and a huge blot of red for a mouth.

Jason took the sidewalk from the street to where he lived, a tall old clapboard house. He went up to his rented studio unit and dropped to the futon. He let his head loll back and stared at the ceiling a moment, then called the service again.

Someone picked up on the fourth ring. “SuiNote, Steve speaking.”

“Hi. My name is Jason. My suicide note isn’t right yet.”

“Your account number?” After checking, Steve said Jason would have to pay again. Jason put the money through. Steve confirmed receipt and restarted the consultation.

“So, Jason, how can I help?”

“It’s too hard on my girlfriend. It should say more about my parents. And my screw-ups.”

“Alright,” Steve said. He paused. “Yes, I see it really goes into Ashley’s infidelity, and how now you won’t be taking her to the Big Game against Stanford. So okay, you want to downplay that. How about when your dad made you smoke cigarettes until you threw up?”

Jason looked at the ashtray on his desk. “No, bigger stuff. What an asshole he is in general, and my mom.”

“Sure. But the foul language fee will bump up the cost.”

Jason said he guessed money didn’t matter now. They worked on the note for over an hour, with Jason incurring greater expense every twenty minutes.

Steve read aloud. “‘My conscience is clear. I’m strong enough now to know the things you did were wrong. I hope you’ll realize you were wrong.’ The implication that you weren’t strong when you were young makes you sound vulnerable. That’ll be good.”

Jason wondered aloud if suicide was the solution.

“Only you can answer that,” Steve said. “It’s a big deal. What you have to decide is will this be your legacy: a well-crafted suicide note that maximizes problems a lot of people would think are completely solvable. It’s your call, man.”

Jason was silent two full minutes. Then he said, “Steve, you still there?”

“I’m here, Jason.”

“Maybe you’re right. I—”

“Time’s up, Jason. I’ll need more money.”

He paid again. “Maybe I shouldn’t have called you guys.”

“No, Jason, calling was good. I’m here to help you write a good suicide note. If it goes unused, that’s fine. Remember, the note’s yours to keep. Once it’s dispatched, you can use it anytime. Suicide is an extremely personal decision, an extremely personal decision that also affects others. You have to be very serious and determined about it. And don’t forget, we’re confidential, so if you decide your life’s worth living—and I think there’s an argument to be made for that—no one has to know you called.”

“Steve, thank you. But I don’t think now is the right time.”

“Okay. That’s cool. I’ll send it as is, and we’re done.”

“I feel kind of stupid now,” Jason said.

“Don’t, man.”

They hung up.

Jason poured a bowl of cereal and ate leaning back against the kitchen sink. His electric Forêt Malheur Ale sign glowed orange and red on the wall, “Oregon’s Truth-Telling Beer!” On the refrigerator were pictures of friends from here at Cal and from high school, including one of him upside down between two girls, the three of them doing keg stands side by side.

He thought about the time he was five, being the assistant while his father and one of his father’s friends repiped the basement. Jason dropped a coupling. It bounced, and fell down into the sump pump. When his dad reached, Jason flinched. Jason saw his father’s friend notice, and his father noticing his friend’s noticing. Nothing was said.

The job was completed in silence except for one moment. Twice while passing a tool Jason trembled. The second time, his father told him to go take a break. When his friend left, his father filled two buckets with five pounds each of dry cement mix and made him hold them in front of himself. Then he took a section of old pressure washer hose and started whipping him.

After he ate he read through Steve’s revision. He paced. He looked at his books. He looked at the clock his grandparents had given him, sitting on its shelf. The face was pearly white, the hands black, the Roman numerals faint gold. The framing was dark and curved. In all, the clock took the shape of a perfect standard distribution bell curve.

He looked at the three mounds of laundry beside the futon, one clean, one kind of clean, one dirty. He emptied ashtrays. He looked at the chemicals and old socks and shirts under the sink. He looked at the unset traps his landlord left under there, for rats, “just in case,” even though Jason had never seen rodents except out by the dumpster. He stared out the open window, at the roofs of neighboring houses and down at pale Korporlundt, turning a wrench that flashed a greasy silver under the lamp.

Jason called SuiNote again.

“SuiNote, Amelia speaking.”

“My life sucks,” Jason said.

“Do you have an account with us?”

“Yes. The name is Jason. KDX51-0721VY.”

“So, Jason, how can I help?”

“My note’s still not right. I thought I wouldn’t need it, but I do.”

“Let’s get going, then.”

Jason heard Korporlundt’s ignition clicking several times, but the engine wouldn’t turn over.

Amelia expanded the section about Jason’s parents. She wrote extensively about an afternoon just before second grade when Jason’s dad passed out while he and Jason were fishing and their boat went over a dam. His dad scrambled atop the overturned boat, but Jason had been thrown farther, and in the current he didn’t make it to shore until he was several miles downriver.

Jason asked Amelia what the note said about him blowing his scholarship.

“Not much,” she said. “But first—”

“What does it say?”

The clock chimed nine o’clock. Amelia read both sentences aloud. Jason said it needed to say a lot more. Amelia said it would, when they were done. But first he would have to pay the traumatization fee.

“The what?” he asked.

“The incident going over the dam, that was a traumatizing story,” she said. “The company requires that we charge a fee.”

“For what?”

“Possible effects of listening to such an occurrence.”

“Listening to that traumatized you,” Jason said.

“No.”

“So what’s the matter?”

“The company requires the fee regardless.”

“So don’t tell them.”

“Calls are monitored for your protection.”

***

“Mr. Jason,” Amelia’s supervisor said, her voice smooth and curved, but hitched to a quick tempo. “I do understand your reluctance but we must charge. If you refuse this the call will be terminated and so will your SuiNote account.”

“You say you’re not traumatized,” Jason said. “Amelia said she wasn’t. What’s the big deal?”

“Mr. Jason, it’s the possibility of traumatization. You share this memory of parental negligence in which you get thrown from a boat in a rushing river and the one person who should have protected you didn’t. Amelia can tell you now that this has no effect on her. She can mean it. But later she goes home and the images roll through her mind, a six-year-old boy, in a boat, shaking his father who’s slumped beside a cooler, the boat getting closer and closer to a dam, the boy shouting, screaming, ‘Dad! Dad!’ shaking him more violently, shouting more loudly, but no success, and the boy and his father go over the dam. They’re thrown. And just like in a car crash where it’s the drunk who doesn’t get hurt, your dad’s able to get hold of the boat but you can’t and you struggle for miles to get to the bank. Mr. Jason, you have no way to assure me that these images won’t tumble over and over in Amelia’s mind. My staff might remain unchanged after hearing such things, but they cannot be expected to.”

“Your staff helps people kill themselves,” Jason said.

“No. My staff gives people the objective eye they need to express why they’re killing themselves.”

There was a knock on Jason’s door. “Jason,” came the voice. “It’s Korps. Can you help me push my car up onto the grass? My roommate’s going to have to get out before I’m up.”

Jason covered his phone and yelled toward the door, “I’m kind of busy, Korps.”

Korporlundt said he was sorry. But his roommate was asleep and anyone else was too drunk. All Jason would have to do, he said through the door, was walk along and steer.

“Really, Korps, find someone else. Right now I can’t help.”

Jason told Amelia’s supervisor that he was going to drop SuiNote. The supervisor said that was Jason’s prerogative but she appreciated his patronage and wanted him to have a high quality suicide note. Maybe, she said, they could compromise.

Jason paid ten percent. Amelia returned.

“Jason,” Amelia asked, “were you using the fee for avoidance? So you wouldn’t have to say what you should say? That you cheated on Ashley? That’s why you downplay her cheating. Because you cheated.”

“What?”

“I was thinking about it,” Amelia said. “You really glossed over that, talking about your dad, the scholarship.”

“I lost a full-ride out-of-state scholarship.”

“You cheated on her, didn’t you?”

“Can you please help me write my note? You know, the reason I called?”

“Jason?”

“The note? Please?”

“I think you were getting a little something and you won’t admit it. You’re not mature enough to be true.”

“Aren’t you supposed to be helping?”

“And,” Amelia said, “I don’t think you really want to commit suicide. I think you called just to unload. Am I right, Jason? That you’re using us? The way you used Ashley? It was one of her friends, wasn’t it? I’m quite psychic. Wait!” She interrupted herself. “There were more, a lot more. And two of them were friends of hers. Maybe she did cheat on you, but it was revenge cheating. Yes. That’s it.”

“Are you finished?” Jason asked.

“Are you?”

There was a shout outdoors. “Help!” It was Korporlundt’s voice. Jason went to the window.

Korporlundt was on his butt at the car’s back bumper. The car sloped down at him. He was pushing against it.

Behind the front tire, someone’s leg stuck out.

Jason took the stairs three at a time. He bounded out to the car and threw the phone in the grass somewhere.

The wheel had edged up on the leg—a woman’s, with jeans that stopped just below the knees—but wasn’t crushing it yet.

“Korps, I’m here.” Jason put his shoulder through the door’s open window and shoved against the frame. The wheel rolled off her.

He shouted back to Korporlundt that they had her free. He looked down and yelled, “Can you slide out now?”

No answer.

“Hey!” he said.

Keeping his shoulder into it, he toe-tapped her leg.

“No fair tiggkling,” the woman said, and laughed.

Jason smelled alcohol.

He asked again if she could slide out.

“You wan’ me wha’?” she said.

Korporlundt said, “She’s hammered, man! Just get her out!”

“Why’d you use her then?”

“It wasn’t a well-thought-out plan!”

“Alright alright, maybe she’s caught. I need to let go to see. Do you have it?”

“Yeah.”

“This car ends up on me, I’ll stop letting you buy me shots when I beat you at foosball.”

“Ha. Come on!”

Jason eased back from the door frame. Korporlundt hove against the weight. The wheel stayed off the woman.

Jason got down and put himself beneath the car. He saw she wasn’t wedged anywhere, or blocked. The white tank top she wore wasn’t snagged on an errant bolt. She was just stuck on her back, drunk. How in the hell did she get so far under?

Jason grabbed her at the waist and tugged.

“Ow!”

“Don’t worry,” Jason said. “I’m getting you out.”

The car slipped.

“Korps!”

“Shit! Got it! But hurry up!”

Jason tugged on the woman, and she complained again. He got himself out from under the car and pulled her clear. “I got her! We’re good!” He ran to the back bumper.

As Jason pushed, Korporlundt shoved off with a big groan and got up and out of the way. “God, my friggin’ head,” Korporlundt said. He pressed the heels of his hands into the back of his neck.

“Eat more sauerkraut,” Jason said, and smiled. Korporlundt walked off a ways and sat down on the grass.

Jason went back to the woman while the car slowly rolled about twenty feet, and petered out.

“Jason,” someone said.

“Hey, Jason,” said someone else.

About fifteen people stood there. One guy held a beer bong. More people emerged from the houses.

Jason got her up. He stood her still, holding her shoulders, steadying her. She had blonde hair almost to her waist. It was soft and silky. Jason looked into her eyes and asked if she was okay.

“Yer kina cute,” she said. She wiped at a smudge on her tank top.

“Yer kina stupid,” Jason said. “What’s your name?”

She looked back up at him. “Bianca. Yer kina cute.”

Jason raised his voice. “Anyone going to claim Bianca?”

Another girl came forward. She had light brown hair and, when she got close, the tiniest freckles on her nose and cheeks. She told Bianca that she had to be more careful. She looked at Jason. “We were at a friend’s. She wandered off. Sorry.” She smiled at him and said, “You’re in Statistics. You’re Jason.”

“Yeah.”

She tilted her head toward Bianca and said, “You saved her.”

“She was fine. Just a little tipsy.”

“No. You saved her. My name’s Heather.” She smiled again.

“Nice to meet you, Heather. She just needed a hand.”

A guy in a Cal Bears cap came up holding Jason’s phone out at him. “Dude, I think somebody’s trying to talk to you.”

Jason smiled at Heather and Bianca before taking the phone.

“Jason,” Amelia was saying. “Jason, are you—”

“I’m here. Everything’s—”

“It sounded like something really bad was happening. Are you hurt?”

“No, it was just a girl who needed a little help. She’s fine now.” Jason covered the phone and looked at Heather. “What are you two doing Saturday?”

Heather smiled and gave a little shrug.

The guy in the Bears cap shouted. “Hey! Holy shit!”

He pointed.

Korporlundt was on his back, not moving.

Korporlundt was dead.

911 would be called, paramedics would arrive, interventions would be begun, and transport made. But he was already done. Statements would be taken, questions asked. Substances would be secreted, bystanders would slink away, a TV truck would pull up. An autopsy would reveal a brain aneurysm, blown, and arterial plaque. But it was already over. Jason would end his call, the women would give him their numbers, he would, around sunup, sleep.

But at this, the moment of discovery, someone dropped down and started chest compressions. Jason ran over and held both sides of Korporlundt’s head. He and the good Samaritan chattered at him, telling him to stay with them, telling him he would be fine.

This story originally appeared, in slightly different form, in Fault Zone: Stepping Up to the Edge, an anthology produced by the California Writers Club, San Francisco & Peninsula branch, Lisa Meltzer Penn, ed., published by Sand Hill Review Press.