by Douglas W. Milliken

It took less than six months for my luck to run out and like a worm under a rock, I was found. Joel. That big brutal fuck. Quite likely the last person I wanted to see. With his fallen prince face and mouth like an open sewer. A smoldering ghost of ruin and violence. Joel and I’d had good times and bad times but our friendship kind of petered off when he went to jail for hassling some young girls, an event that I’d heard he blamed me for on account of I was there when it started and was in a unique position to stop it or join in and instead chose to walk away. Apparently he thought I ought to’ve gone to jail, too. He’s probably right. Instead, I left town and hitched around the country, from West Virginia to Northern California, and after a year of shambling this way and that, I somehow ended up right where I began in our little Northeastern coastal city. I guess the plan was to start over with some things left behind in my past, and maybe in the back of my mind I hoped that, if I made a clean wash of things, I could maybe someday have my family back. Joel was not part of my plan to start over. Joel was part of what I hoped to leave behind.

It was in the bleak final run of February when Joel found me on the street. He was standing outside a Chinese restaurant with a newspaper and coffee in his hands. I was heading home from working for the Rhys family. Everyone knew the Rhyses were criminals but they also gave a lot back to the community—funding the construction of a new pool for the high school, restoring a derelict park uptown, that sort of thing—and so thrived without too much trouble. Some days I’d be paired up with two other weirdos, a young thug named Chin and a disgraced acrobat named Breast, running packages across town or unloading trucks or whatever. But the day Joel found me I’d mostly spent at the family’s waterfront clubhouse, which was pretty much an Elks Lodge for all the smiled-upon partners of the Rhys family. I’d been asked to perform dishwashing duties, but mostly I drank coffee and chatted with whoever passed through the kitchen. It was mid-afternoon so almost completely dark when I was cut loose: I was hungry and caffeine-jittery and just wanted to go home when Joel grabbed my shoulder with one gigantic hand.

“Christ Almighty, Coleman.” His voice was all raspy as if he’d been shouting. “You planning on just walking right past me? Not even a goddamn hello?” But he’d always sounded that way.

My fake smile felt lame on my face. I took his hand from my shoulder and shook it. It was like a single enormous callus. His nose looked like it’d been broken again and his teeth seemed more crooked than I remembered. Even for a big guy, jail couldn’t be easy. Everyone’s always got something they want to get over on you. Joel and I didn’t say anything for a while, just shaking hands and staring each other down, him with his teeth and me with my cringe. Like we both knew this moment could only get worse if we let it go on. So we let it go on. Then Joel all at once insisted that we get a beer around the corner, in celebration of our impromptu reunion. But the way he kept smiling didn’t feel terribly celebratory. It was a calculation. There was no way I could say no. Joel rolled his newspaper into a tube and stuffed it inside his greasy coat. He threw his coffee on the shoes of a passing stranger. Whoever it was just kept walking, didn’t even look back. Joel laid his enormous hand on my shoulder again and led me across the street.

The place we went to was an old haunt of ours called The Poptimistic. It was originally opened as some kind of disco back in the ’80s, but that didn’t last too long: humpy beats and a stupid name can’t control the clientele who will call your bar their home. All that remained of those sweaty disco days was a grimy mirror ball and colored panels on the dance floor that lit up whenever you stepped on them. But of course, the dance floor was empty. The Poptimistic had become the crusty sort of pub that catered to an unlikely mix of the down and out. There were crippled manual laborers who’d retired into geriatric day drinkers and there were middle-aged college professors rinsing themselves out of a job. Scrawny skinheads with shitty breath and modern cowboys who’d follow you into the bathroom just to watch you piss. If a wino could hold it steady and didn’t stink too bad, he could stay until his money ran out. It was one of the places that, in the old days, Joel and I had always been allowed to pass. Apparently, nothing had changed. The beers still cost a buck.

Joel sidled up to the bar and flashed his horrible teeth at the biker chick working the taps. I can remember when she used to be cute. I bet if you cut her leathery skin open now, all that’d pour out is cigarette butts and crumpled IOUs dusted in colorless ash. Joel ordered us each a shot and a beer, and somehow I knew right then that I was going to get stuck with the bill. Sometimes life doesn’t care what you want. In fact, it never does. The shots came and we touched glasses, and just as the cheap well vodka touched my lips, Joel toasted to the good old days, and all at once I felt like throwing up.

Two winters prior to all this, Joel and I had lived together in the shittiest apartment imaginable. Whoever had lived there before us had been big into breeding pit bulls. The place never recovered. It always smelled of dog shit, and whenever a muggy thaw took hold, the stink rose thick and gagging from the stained carpets and bubbled linoleum. We spent that winter selling pills to teenage hoodlums and pulling the occasional rip-off. Once we somehow chanced upon a free duffle bag of jimson weed, which we cut with some cheap commercial dope and sold at a premium price. Kids lost their minds on that garbage and came back begging for more. They had no idea they were smoking poison. These were the months and weeks immediately following the divorce and were not very good times, certainly nothing I wanted much to remember—it was that same winter that Joel and I had our original falling out, when we got drunk on malt liquor down by the tracks in a blizzard and I left him behind when he passed out in the snow: he nearly died out there of exposure and rightly blamed me for it (this event was not much helped by the fact that I soon after began sleeping with his sister, all of which is strong evidence that I’m not a very good friend)—but Joel really wanted to reminisce about those days. Like some sick nostalgia machine, savoring every one of our awful wrong turns. In particular, he wanted to talk about the Chinamen.

“Goddamn, that was a sweet deal,” he kept saying, slapping the bar and gesturing for the bartender to bring us another round. “We should have done that more often. So easy!”

Personally, I felt like once was once too much. There was an abandoned elementary school on the top of the hill that we’d found out was being used as a secret meeting place for gays of the Asian business community. As discreet as these guys were, it was still pretty easy figuring out their routine: I’m sure their wives all complained about the late business meetings that kept them away from home two or three nights a week. One afternoon, Joel and I sneaked into the school and hunkered down in the boys’ locker room, each of us with a big, chunky plumber’s wrench. It hurt just looking at those things. I’m not sure why we thought the locker room was the place to hide: I guess it just made an intuitive sort of sense. Whoever these guys were, they kept the place pretty clean. No condoms or anything on the floors. Just the lingering stink of adolescent piss. At just about happy hour, we heard the school’s big front doors open and close, then footfalls clapping down the main hall, and Joel and I waited until right then to blow two massive rails. A few seconds later, three young Asian men came in, wearing nice dark suits and carrying briefcases. They looked good. Clean and very excited. They never saw us coming. We jumped out and swung our wrenches hard into two of the men’s stomachs, though my aim might have been off as it felt more like I shattered his pelvis than creamed his guts. The third guy took one step backward toward the door and started to shout something, but Joel knocked out all his teeth at which point he wasn’t shouting anything. The coke burning through my brain made the whole scene hilarious. A minute later, the three guys were knocked out on the pissy locker room floor and Joel and I were a couple hundred dollars richer. I even swapped clothes with the tallest of the men: I went home in a nice new suit and he went home in my rags. At the time, it didn’t feel like anything. It’s amazing what drugs can do.

Joel really liked telling that story. It was all he wanted to talk about. The sick look on those guys’ faces when the wrenches plowed into their guts. The way the one guy’s bloody teeth sprayed all across the room. Joel couldn’t get enough of it. I sat beside him at the bar feeling sick, from the cheap vodka or the memory, I couldn’t tell. We had done this to strangers. I’d cleaned myself since of everything but the booze and was trying to start my life toward something like living again, trying to be better if not entirely good. But the facts remain. I did this. We deserved whatever we got. Joel laughed and made some joke about chow mein and brown sauce. The bartender didn’t like us anymore. Joel ordered another round. Then he asked me:

“So where you living these days, Coley old boy?”

This was information I had no intention of giving out. Not even my partners Breast and Chin knew I had my own place. I figured, if they knew, they’d sooner or later want to come stay with me. And in those days, more than anything, I wanted to be alone. The eldest Rhys brother knew where I lived, but only because he had pulled some strings to get me into an apartment. The family didn’t own the building, but they might as well have. The super showed me the space and after a quick walk through, I took it. There was a living room with a busted couch and a TV and a window that looked out onto the parking lot of a fast food burger joint. There was a kitchen with a toilet next to the fridge. That was it. Like they’d taken a full apartment and chopped it in half. It was the nicest place I’d lived since you kicked me out of our house three years ago. Or anyway, it was mine.

But now I could feel that something was turning. It had always been there. But I hadn’t wanted to see. It’s not enough to just want to get better. It costs. You find a tunnel and hunker down in the dark. You think you’re hidden and safe. Then too late, you see the light coming fast. It bears down on you. There’s nothing you can do but submit.

Our last round came and I took the shot and felt the whole room spin. Then I told Joel where I lived.

Joel smiled and clapped me on the back. Then he said he had to piss. He got off his stool and walked past me. I knew he wasn’t coming back.

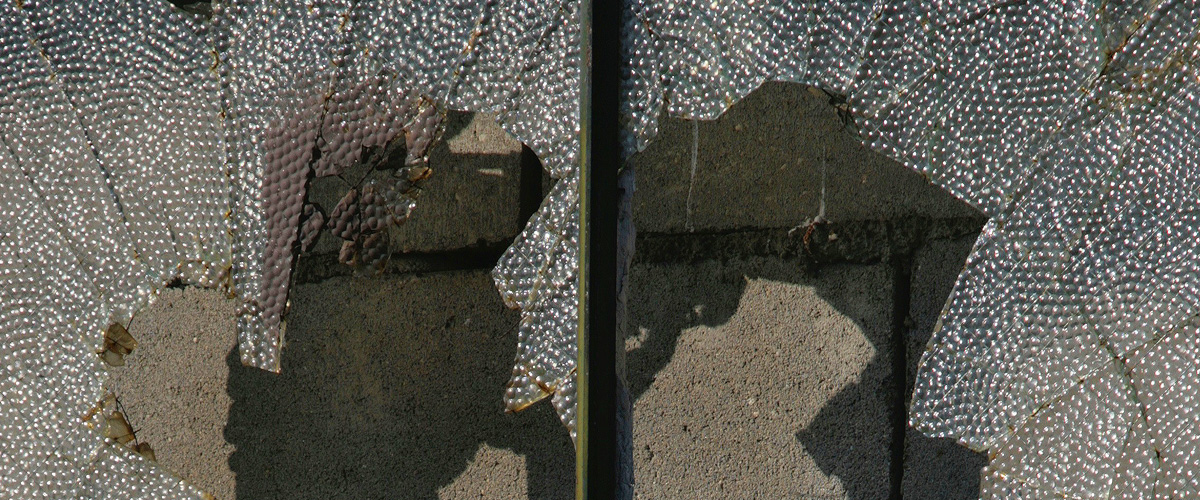

I leaned against the bar until the blurring tilt-a-whirl lights clicked back into place. Then I paid for our drinks and left. It was dark out now. I walked down to the waterfront and watched the ferries coming in, watched their lights reflecting on the water. The cold milk of an evening fog was rolling across the bay. I threw up off the pier. Then a thousand screaming seagulls descended. I didn’t feel any better. I watched the birds eat my vomit, then I wandered back up from the waterfront and through town. No one, it seemed, was on the streets. It was cold. I passed my building on the opposite sidewalk three or four times, but eventually I had to go in. I don’t know if I was scared or just giving him time. While I fumbled with the keys to my building, a big black shape chugged out of the alley, and I don’t know if I saw it or just knew that what the shadow held in its hand was a plumber’s wrench. I didn’t try to stop it. The chunky end of it caught me square in the guts, then crashed hard again into my ribs, and for a second I couldn’t see anything and couldn’t breathe. Then the wrench clipped my right knee and I went down.

Joel didn’t rob me. He didn’t say anything. He kicked me once hard in the side of the head, then dropped the wrench and walked away. I lay there on the sidewalk outside my building and puked on myself a little. But I hadn’t anything left inside. Some people walked past me. I didn’t think I could stand up. I crawled to the door and grabbed the handle and pulled my body up over my feet. I keyed into my building where the fluorescent lights shined sick and chemo-anemic. I collapsed into the elevator and somehow made it to my apartment, chained and dead-bolted the door, dragged my ruined leg into the living room. Turned on the TV so blue light flooded the room. Local news. I laid myself across my couch. I thought for certain I would die. My body kept trying to puke, but all I could do was spasm and choke. Outside, some kids were shouting in the burger joint’s parking lot. Someone wanted their money. Too bad. It seemed pretty clear to me right then that I would never see my daughter again. All my organs felt like they’d been popped and split open. My vision swam and dissolved with my concussion’s dull throb. The weatherman said more cold weather was coming. But I could already feel it. Back to you, Chad. I closed my eyes and told myself not to die. But I knew I probably would.

I slept for three days after that. I guess they call that a coma. Then I went back to work. Chauffeuring the Rhys brothers around town with a pair of dark sunglasses to hide my busted face. I wrapped my torso in a long Ace bandage to keep my broken ribs from swimming. I did not tell anyone what happened, least of all my employers. The Rhyses would’ve put Joel in a wheelchair for good. I’d already done my friend enough harm. And anyway, by summer, I was fine. Just a little worse in my limp. But some nights when I wake up in the glow of my TV, I think it’s happening again. Or really: think it’s happening still. My skull crunched. My ribs and my organs bruised into a jelly. All my fluids leaking into places they have no reason to ever go. Brain swelling and about to shut down. The flashing TV light just my synapses burning out. I wake up to a panic seizing me and can’t breathe, can’t move. The despair of the moment makes me cry. My recovery is a dream that’s dispelled before dying. I wanted it so bad. But now it’s gone. I’ll never get better of all the things I’ve done wrong. I thought I would get there. I almost did. But Joel got me good and will always have gotten me. I’m getting exactly what I deserve.